The Important Path Towards Allyship

A small guide on how to help people reveal their own unconscious biases, how to find the right ambassadors, and how to make sure employment resource groups work towards integration, not segregation.

It is a statement that would make both war strategists and C-level executives nod in agreement: every worthy cause requires plenty of allies. And particularly when we talk about ways to make the workforce more diverse, equitable and inclusive, little can be achieved without making sure the policies and avenues themselves are, in fact, inclusive to all employees.

There is no doubt that organisations that focus on building bridges between the underrepresented or marginalised communities they want to empower, and employees or leaders from the dominant culture that want to support them, end up having more robust and effective DEIB policies. Plenty of data goes to show the power of allyship in practice: a 2017 study showed that among companies where men are actively involved in gender diversity, 96% report progress. In organisations where the opposite is true, only 30% show progress.

The same is true for the business case of allyship which -much like the business case for DEIB overall- shows a pathway towards a happier and more productive workforce. According to a survey brought up in a 2022 HBR article, employees of organisations which foster strong allyship and inclusion cultures are 50% less likely to leave, 56% more likely to improve their performance, 75% less likely to take a sick day, and up to 167% more likely to recommend their organisations as great places to work.

So it seems like a no-brainer that building allyship should be a quick fix solution for an inclusive workforce, right? Actually, as a series of interviews we conducted revealed, it’s not that simple. For starters, allyship runs the risk of being too nebulous and too vague of a concept. An overzealous ally may end up silencing the group that they claim to support, an overly performative one may provide mentorship and support that is too superficial or sporadic.

Then there is also, of course, the question of the chicken or the egg: is allyship a means to an end, or a result of actions already taken?

As catchy of a concept as it may sound, it’s clear that allyship needs further analysis and a clearer roadmap for companies to put it in place effectively. Read on as we set out to explore what the ultimate goal of allyship should be, when and where it works best, who should be the main drivers of change, and how it can truly have a transformative impact on the workforce.

Step one: coming to terms with our unconscious bias

As much as everybody would like to pride themselves in being a worthy ally towards a less dominant group -be it women, LGBTQI+ individuals, people with disabilities or different ethnicities - it is a process much easier said than done. A DEIB leader with over a decade of experience, in companies from various industries and across different regions of Europe, phrased it best when talking to us about the biggest challenge of allyship programs.

“Allyship is a challenging topic, and a rather difficult one to achieve because it presumes that, we in general, have understood all our own unconscious biases. Of course you have people that may raise their hands and say, “I totally support diversity and inclusion”; But based on my experience, most of the people who will raise their hands, are not actually visibly and practically supportive. Understanding one’s unconscious biases is an incredibly difficult thing to do”.

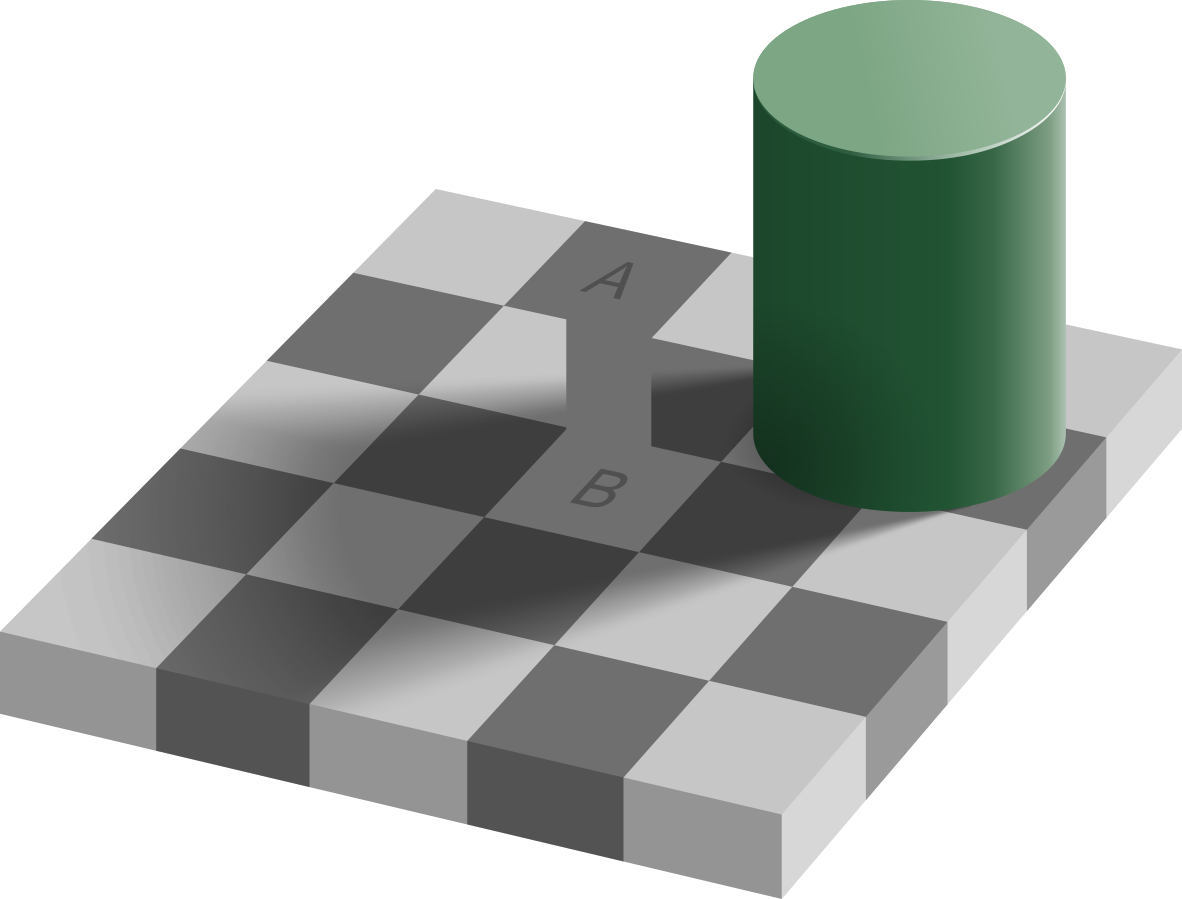

To fully understand the gripping power that an unconscious bias holds over the human brain, it’s helpful to take things to the abstract. Take a look at the image below.

It should be crystal clear what you see in front of you: a chessboard with white and gray squares, a colorful cylindrical object casting shadow to a part of it, and two individual squares titled A and B. It should also be abundantly clear that square A is grey, and square B is white, correct?

Not quite. Take a look at the image below, slightly modified to help you realize why.

Turns out, in reality both squares actually share the same color: an identical shade of light grey.

This mind-frying experiment is called the “Checker shadow illusion”, and it is the result of the studies of Edward H. Adelson, a professor of vision science at MIT who published his optical illusion in 1995.

It is a visual experiment used very often by Cécile Kossoff -Group Chief Brand, Marketing, Communication and Sustainability Officer at Europ Assistance, and a teacher at HEC business school with over 15 years of research and engagement on Diversity and Inclusion- when she addresses crowds at big DEIB conferences. As she confessed to us, she performed this illusion in front of hundreds of smart, very rational business leaders in the room, who stared collectively perplexed at the visual paradox of the images side to side. “Their brains are freaking”, she says.

The scientific explanation behind the optical illusion, as she points out, is that “our visual system physically distorts the external reality in a way, to compensate for how things should “normally” look like - in this case under the situation of a shadow cast on a chess board. Essentially, the brain has integrated the information that if you have a chess board, you must have light and dark squares, and if you have an object on top of it, it should cast a certain shadow. And so our own vision system will adjust the image that it actually sees, and perceives the squares as two different shades, in order to please the brain”.

Cécile's use of the two images side to side drives home a very crucial point about building allyship. “The experience essentially shows that telling people what’s good and fair, to make them aware of what needs to change, is not going to work alone. Their biases are by design unconscious, so they won’t change just by you telling them. They will always keep seeing reality in a certain way”.

“So of course, we have to build awareness, pedagogy, and education programs. But it's not enough. The first thing to do is to immerse people in a different situation than their own. When they live differently, their mindset will change because the situation they will experience will be different”.

In other words, Cécile borrows the visual experiment to show that allyship can truly work only when individuals are invited to take an active role in identifying, and then correcting their own blind spots. (And that sometimes, abstractions can actually help reveal reality).

Employment Resource Groups: a stepping stone towards allyship

Most organisations that aim to embed allyship initiatives into their DEIB practices have a common vehicle and starting point: Employment Resource Groups. ERGs have been around since the 1960s, when a group of Black Xerox employees first assembled to discuss race-based tension in the workplace, and they essentially refer to employee-led groups, often voluntary, whose aim is to foster a diverse, inclusive workplace aligned with the organisations they serve.

They are essentially networks, usually led and participated in by employees who share a common characteristic - whether it's gender, sexuality, ethnicity, religious affiliation, lifestyle, or interest -, and they exist to provide support and help in personal or career development within that organisation. Think of them as a form of safe space, where employees can bring their whole selves to the table and identify pain points in their inclusivity and belonging.

George Filtsos, Senior HR Manager at Kaizen Gaming, is currently in the exciting process of starting such a Diversity & Inclusion group in his organisation, to support other LGBTQ+ individuals at work. “We already have a network group for women in the workforce, as well as a self-managed LGBTQI+ team that was created bottoms-up, stemming from the need for the people to connect with each other and to feel the psychological “safety of the masses” if you will - something very important in inclusive work environments”, he tells us, adding with enthusiasm, that the group has quickly gained a lot of fraction and will soon receive the formality of an D&I group.

“It has helped people tremendously to discuss things that are usually not in the awareness radar of people not belonging to a LGBTQ+ group: the challenges of entering and integrating into the office, the ways that language can become more inclusive at work. These observations led us to create a webinar, with volunteers from our group, where we will discuss how to build bridges for LGBTQI+ people in the workforce, and will highlight some of the experiences that came up in our discussions”.

From the experience of the Women network group in his organisation, George understands that at a certain level of maturity and after pointing out shared experiences and pain points, it becomes time for the networks to become more open and extroverted, and to reach out to leadership with actionable proposals. “Eventually, these employee groups are not just a safe space, but a way to unearth things that are hidden, to make people go “we don’t know what we don’t know”. And the most important thing is linking these discussions to the context of our organisation”, he says. He brings the example of gender pay parity, women network allyship with senior management to sponsor an equal pay certification for the organisation, to examine to what extent the organisation is an equal pay provider and to then advertise it internally, and build further allyship around the cause, set to launch later in the year.

Another individual, a Principal consultant with experience across different regions, agreed that ERGs need to have leadership involved, arguing that in cases where they don’t they may even risk a backfire.”Creating an ERG without having an overall strategy or sponsorship of DEIB policies from the top, will probably not be successful”, he argues. “It is good in a sense, because you create a pocket, a small group where people can discuss and feel like themselves. But at the same time, this ERG becomes visible, and anyone who participates may also be stigmatised if the culture and mindset haven’t changed, if training and education aren’t simultaneously being scaled across the organisation”.

Cécile, on her part, also believes that a central part of allyship is opening up networks and communities to include the other, and that ERGs are a stepping stone towards building an overall inclusive culture. “Let’s take gender equality as an example: to successfully create allyship, as a women’s group you need to invite and include men in your actions. So include the other sides of your world in your discussions, in your groups, in your events so that they mix and they can hear your stories. Of course, an ERG is essential in highlighting the issues of your community, but at the end of the day it's more about how we mix and interact as people”.

The right place and the right allies

Finding the right timing to build allyship is an important question that ERGs need to answer. Equally important is the question of the right place, and particularly for companies that are active across different countries, regions or geographies. The DEIB leader who spoke to us about unconscious biases stressed that, regardless of what a company may state in its policy and training, it needs to keep in mind that people in different countries and from different cultures have different norms and perceive information in different ways. Whatever one defines as a DEIB strategy on a global level needs to be localised, taking into consideration cultural norms, local regulation, and the sensitivities of any particular group.

“If we tie this back to allyship, you can definitely identify central people in different countries, but then each country or region needs to have its own allyship pockets” he suggests. “You can visualise this as having a Global Alliance, that has branches in the different countries and regions and engages the core public, but then also spreads down to different individual and localised alliance circles. You basically cannot think of allies as a global narrative: you always have to think of it as something that needs to take into consideration the local perspective and the different cultural norms that you have”.

In terms of who would make the best ambassadors, Cécile suggests identifying top management individuals who can combine mentoring and sponsoring - those with the potential to not just coach or advise someone but to actually advocate, to defend someone's case or to build a case for promotion, and so on. She also thinks that sometimes, allies can be found, or rather cultivated, even in the most unexpected places.

“It is important that we are engaging the people who actually are different and see things differently. Say I want to work with an executive committee to start an initiative on gender diversity: usually, you identify the profiles of the executive committee members, and you will always end up having one or two or three people who are not really committed to your cause. What I have found is that often, if you suggest to those who may be further away from your case to lead a change initiative, they become responsible for it, they feel they start to have part of the ownership over it. And eventually, they are actually acting on it.

“We've seen a lot of people change. Leaders change their minds and start to actually act on the topic at hand, because they were given the responsibility for it at the top level”.

Allyship can be life-changing

It has probably become clear by now that, despite its potential, allyship needs to work as a tool in the general toolkit of a DEIB strategy in an organisation. Cécile actually includes it as a simple sub-step in a five-pillar plan to successfully create inclusive and gender-neutral environments. It includes CEO and management commitment, transparency and indicators (because “you can expect only what you inspect” as she points out), women’s leadership development, diversity-enabling infrastructure and setting inclusive processes and mindsets - and allyship is actually only a subcategory of a category of a pillar.

“The best practice is to put in place objective data, and objective processes that will make the decision making the best one, not just the one that suits the dominant models and my brain, because my brain only knows that” she says, while underlining the need for allyship to be grounded in a process-driven system. “You see, a lot of people think that you change how people behave by changing their mindset, right? And that if we tell them, if we educate them, we train them to think differently, they will behave better in a different way. Actually, it's not exactly right: it often works in the other way around. You create a change in the behaviors through law or good processes - then people experience a different perspective than the one they anticipated, and their mindset will change”.

As diligent and thorough as it may need to be, there is no doubt that when the puzzle piece of allyship is properly built, it can complete the jigsaw of inclusiveness and belonging in an organisation. It amplifies the benefits of hiring and retaining top talent of all shapes and sizes. It fosters happier and more productive collaborations. It enhances candor in the workforce, reduces friction, and helps all employees thrive.

Proper allyship can also be life changing, as George highlighted when concluding his thoughts, by sharing a touching personal story. “Allyship in practice has to do with being visible, feeling normal and included. It has to do with receiving the same questions about your personal life as everybody else in the office, understanding that it is more than OK to bring your partner at a company event, feeling that nobody will pressure you to come out, being surrounded by a culture of equality in how every single individual is treated. Actually, my very own personal coming out was very much influenced by how I was seen in my previous company in London: the idea that you are seen, heard by your colleagues, that you can feel part of the work team in the same way that everybody else was. This was quite radical for me on a personal level - it literally changed the way I see myself”.

Thank you for reading this week’s Uncensored article, the second of our Depolarizing Diversity series. In case you missed it, check out Part I where we discuss the most common pitfall for DEIB: when HR is the (only) one pushing it. Stay tuned for Part III, where we will be shedding light at the most often forgotten and underrepresented groups in the quest towards diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging.